Share This Article!

Related Articles

Roots Grow Deep

By: Gavin Oliver

Scott Brame has been a professor at Clemson University for 20 years, but the last place he wants to be is in the classroom. As part of his course in environmental science, Brame and his students have been spending time outside the classroom in the area surrounding Lightsey Bridge on the east side of Clemson University’s campus. Brame — a former petroleum exploration geologist and current assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Engineering and Earth Science — is working with students in his Environmental Science and Policy (ENSP 2000) class to restore the integrity of a local ecosystem.

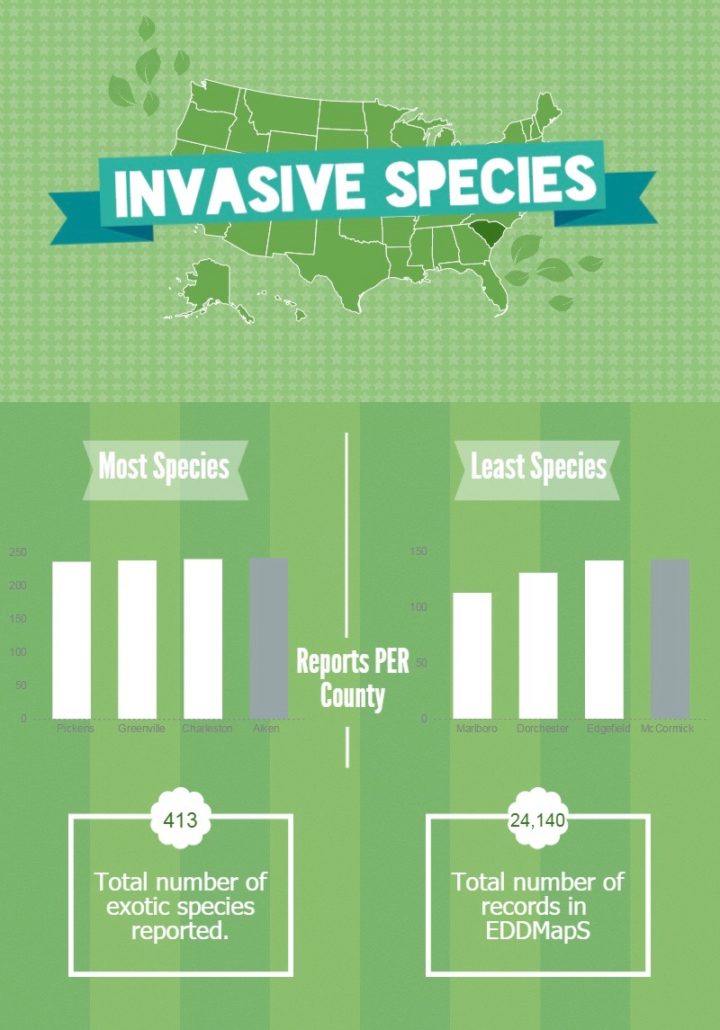

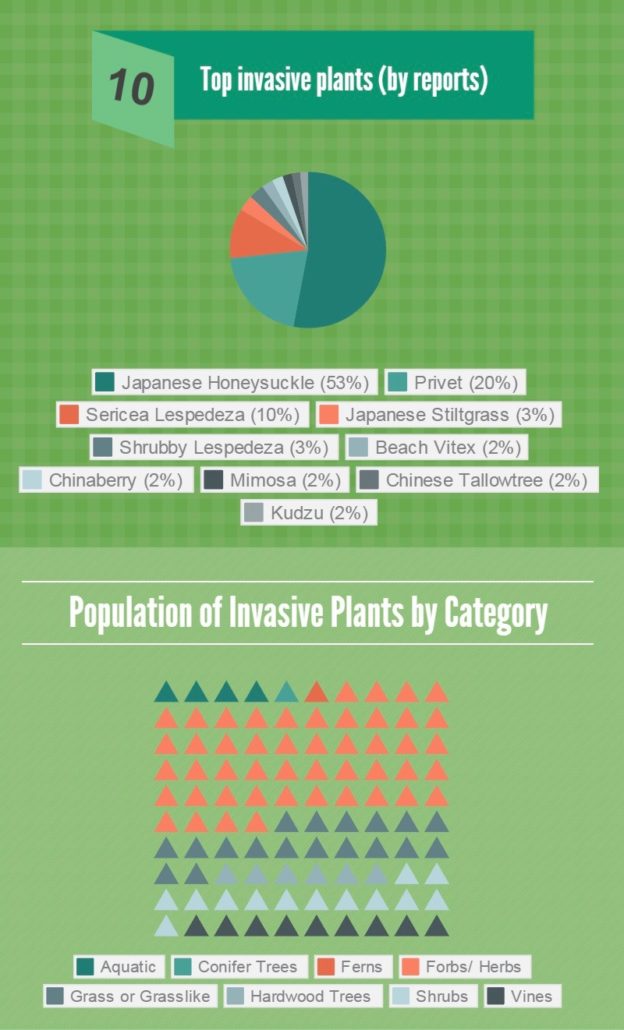

In the watershed around Lightsey Bridge, the first priority is in removing invasive species. This work is being coordinated with fellow Clemson assistant professor Cal Sawyer. Brame’s class seeks to remove the invasive species that now choke the forest adjacent to the stream, especially silverthorn bushes with their inch-long thorns and other non-native ornamental bushes like nandina that escaped from cultivation and have overtaken the natural system. Sawyer, Associate Director of the Center for Watershed Excellence, received a grant from Clemson University to restore the watershed. Sawyer’s vision is to establish a natural state that would create favorable growth conditions for native species. “The native species can’t compete with the invasives,”Brame said. “The non-native species grow too fast. They don’t have natural predators. Left alone, they crowd out native species and will eventually dominate the ecosystem.” Removing invasive species is beneficial to both the ecosystem and to people roaming Clemson’s campus. Intrinsically, the removal of invasive species in the ecosystem allows plants to reach their natural stability and the ecosystem as a whole to progress in a natural state as much as possible within its location on campus. “It’s called community stability, and it’s going to be an unstable community until we remove those plants,” Brame said. “Once you establish the plants, then insects and animals can also become a part of that community. It’ll never be a fully functioning ecosystem because it’s still pretty much in the middle of a developed area, but at least it will look natural and it’ll have the ability to restore as much as it could.”

“The native species can’t compete with the invasives,”Brame said. “The non-native species grow too fast. They don’t have natural predators. Left alone, they crowd out native species and will eventually dominate the ecosystem.”

Furthermore, an area free of invasives means there is potential for the ecosystem to become an enticing spot members of the Clemson community can enjoy. “These areas that have been invaded by invasive plant species, they’re not appealing to people,” Brame said. “Ideally, this would be a nice, open normal-looking watershed with a path and maybe some benches, and people could enjoy it. It would be inviting. In its current state, it’s not. So there’s sort of the human aspect of it.” Brame hopes to continue engaging students in this project and to provide hands-on experiences for students in ways that directly benefit ecosystems as well as the students’ GPAs. “I’ve never actually done a service-learning project before last semester, not like this,” Brame said. “I’m out here with the students in the field, working side by side. My goal is to cultivate a relationship with them beyond what they would get just by interacting with me in a formal setting like a classroom. I believe that experiences of this nature give students an extra dimensionality to the material we talk about in class.” Lindsay Seel became a part of this hands-on service-learning experience last semester. Walking towards the site with her peers on the first day, she was surprised by the sheer number of invasive plants Brame said needed to be removed. However, just two hours later, she looked upon an improved ecosystem. Seel said the hardest part involved cutting free the deeply entangled bushes and untangling the vines that had wrapped themselves around native plants. “Once the group got into a groove, though, it was extremely satisfying to pull a whole plant out and drag it away,” Seel said. “At the end of two hours, the amount of difference we made was definitely noticeable, and it was cool to know that I was part of that.”

Besides benefitting Clemson’s campus, Brame feels his class is benefitting from the process of experiential education, and this is evidenced furthermore by the annual field trips he leads. In March, Brame accompanied the Geology 3750 class as it investigated the geology of Andros Island in the Bahamas. In May 2014, he led a class to southern Utah and in June 2015, he took another group to examine the geology and ecosystems of western Oregon. While the locations and tasks involved in Brame’s projects vary, he constantly strives to achieve the same goal of conserving ecosystems while also teaching students the importance of the work before them. “Instead of being a dispassionate scientist who never takes a stand, we need to get involved,” Brame said. “The lesson of conservation biology is that you have a responsibility to take action when you know more about an issue than the average person. You understand the consequences of not being involved.” Back at Lightsey Bridge, Brame pointed to the expansive land surrounding the stream and expressed there is much more work to be done — enough, he said, to keep him and his classes occupied for the remainder of his career at Clemson. “I’ll probably be doing this until I retire and still not be finished.” Brame said.

Q & A with Students

Cayce Helderman

Q: What is your favorite part of the class (ENSP 2000)?

A: While I really like the class as a whole, my favorite part would have to be how Dr. Brame teaches the material. Dr. Brame engages us with the information. I like the fact he makes us really think about the problem at hand and just doesn’t list off facts. He uses a lot of visuals and makes us really think about what that visual is trying to represent.

Jane Gragg

Q: What is your favorite part of the class (ENSP 2000)?

A: My favorite part of this class was learning about topics that I wouldn’t normally come across in my major classes. As a Polymeric Materials Engineering major at Clemson University, I learn a lot about how materials are created — both on a molecular and physical level, and what bi-products they produce. This class has informed me about the effects that products have on the environment after they have to be discarded, and when they are being made. A message that I have received from the class is to be aware that things are not always as they seem. In order to live our normal daily lives, so much energy must be spent. That energy must be taken from somewhere, and it is being taken from the Earth by loss of biodiversity and increased pollution. I am also a member of the Clemson Biofuels Creative Inquiry team. This semester, ENSP 2000 and Biofuels both have given me a new outlook on my role as an engineer. I am now very aware that my decisions as an engineer will make an impact on the environment and on other lives.

Written By: Gavin Oliver

Gavin Oliver was a junior English major with a concentration in Writing and Publication Studies and a minor in Sports Communication. He also interned with a few sports media outlets in The (Seneca) Journal, IPTAY Athletic Media and Tiger Illustrated. He also worked in Strode Tower as a Student Assistant for the Business Support Services office of the College of Arts, Architecture and Humanities.