Share This Article!

Related Articles

Faculty Spotlight: Advocating for a Different Kind of Service

By: Lauren Kirchenheiter

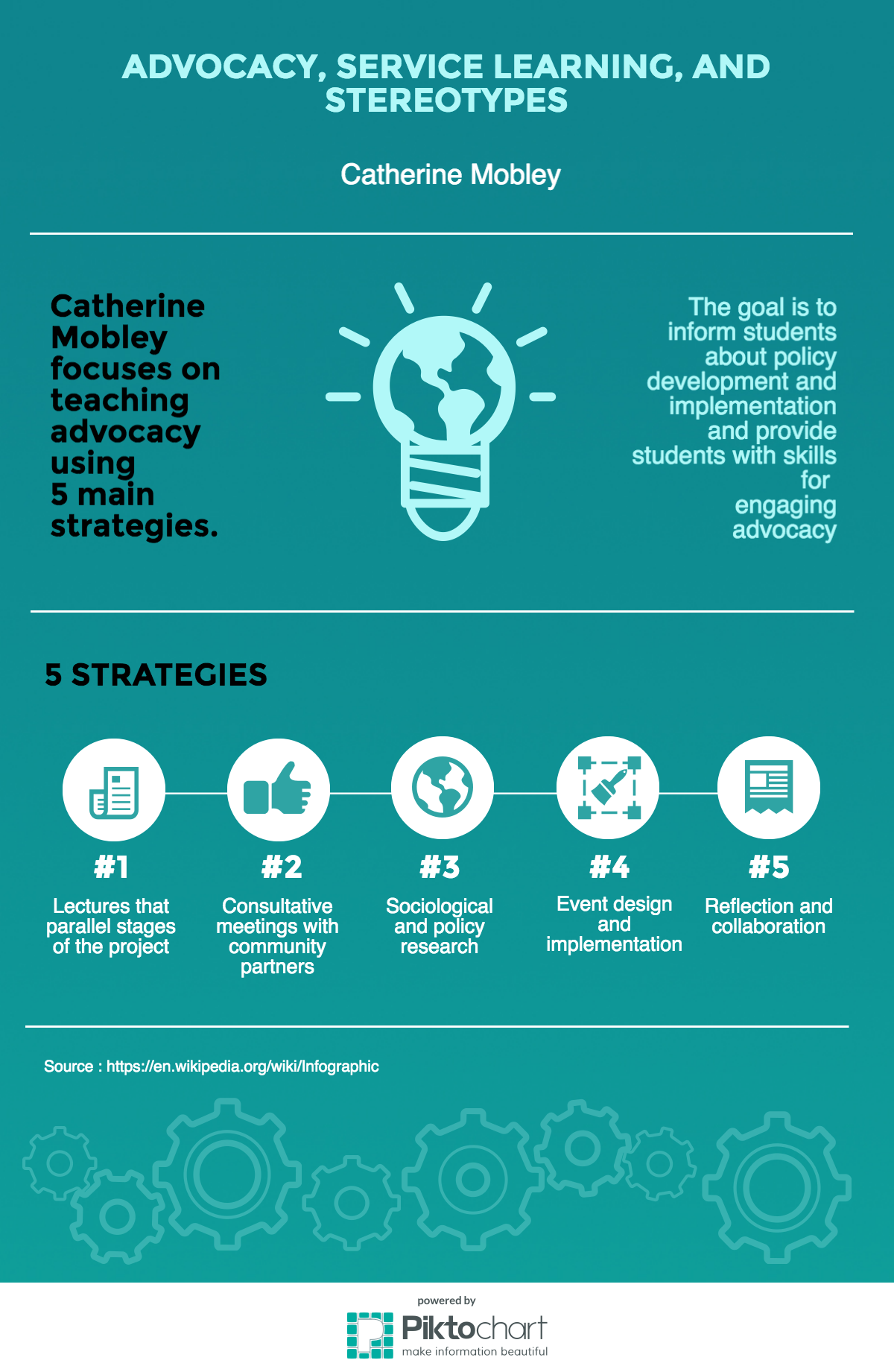

When most people think of service-learning, they picture students going out and taking physical action in the community — like building houses or working at a soup kitchen — but Clemson Sociology Professor Catherine Mobley wants to spread the focus of service learning, reaching beyond the traditional model of service to emphasize an advocacy-based approach. According to Mobley, the advocacy model of service learning looks upstream to the larger issues and policies creating that need in the first place.

For example, working at a soup kitchen resolves an immediate need by providing food for the hungry. However, the advocacy model would involve delving deeper into the inherent social issues that cause hunger. By looking at what policies might have led to these social issues and by advocating for change within these policies, one could essentially eradicate the need for soup kitchens entirely. Mobley is constantly seeking ways to implement this advocacy model of service learning in her career today as a volunteer, sociologist, and professor.

We asked Mobley to share with us her background, her passion, and her advice for other faculty who are interested in implementing an advocacy-based approach to service learning.

Mobley’s Journey Back to Clemson

Mobley has been extensively involved in service learning throughout her career. Her interest began at the University of Maryland, where she earned her Ph.D. in Sociology. As a graduate student instructor, she wanted to come up with captivating ways of communicating her love and passion for sociology while also tapping into her desire to make a positive difference. She found that many topics she covered in her sociology classes, especially those related to inequality and social problems, were perfect for students to explore through service learning. “I think students seeing social issues first-hand is more powerful and complements my theoretical approach in the classroom,” Mobley said.

Twelve years after completing her undergraduate degree at Clemson University, Mobley returned to interview for a faculty position. Having graduated from Clemson, she had some existing knowledge of service-learning efforts in the area, and immediately began searching for opportunities. She felt reassured when she found others who also supported and celebrated this teaching technique at Clemson.

Mobley is especially passionate about her past work with United Housing Connections, formerly the Upstate Homeless Coalition. In the fall of 2001, Mobley launched a project entitled “Breaking Ground: Engaging Undergraduates in Social Change through the Development of Learning Communities with the Homeless.” In an attempt to break down stereotypes that have negatively impacted policy on homelessness, the project required students to form partnerships with advocates and homeless clients to raise public awareness for homelessness and organize advocacy and fundraising events for the agency.

It is now twenty years since Mobley’s return to Clemson, and she remains passionate about her work, always looking toward the future. She is excited about the possibility of exploring new service-learning opportunities in the area of affordable housing as she feels there is still much that needs to be done, and her focus would be more on the advocacy model this time around. For example, she would have students conduct research, surveys or needs assessments for United Housing Connections. She also hopes to incorporate service learning into another passion—environmental sociology.

Partnership, Respect, and Advocacy: Building a Foundation for Effective Service Learning

Not only has service learning impacted Mobley’s career path and community involvement, but incorporating service learning into her approach to research and teaching has challenged her in the classroom as well. “When you do something like service learning, you are introducing uncertainty in the classroom and potential chaos,” she confessed. Mobley has had to handle everything from the logistics of creating opportunities for 35 or 50 different students, to raising issues and topics that might be passed over in more traditional classes. “It keeps me on my toes. I welcomed that uncertainty and that wrestling with questions that might not come up otherwise,” she said.

While she does not currently teach any courses directly involving the traditional model of service learning, Mobley highlights many of the same principles in her field placement and internship class, which has an applied dimension within the community. These principles of effective service learning include agency partnership, respect for difference, and more deeply examining the causes of social problems. Mobley explained that non-service-learning-specific courses can still employ these principles as a framework for community involvement.

According to Mobley, forming a partnership with an agency is the first step, and she says it is important to “start where they are.” Mobley advises faculty members to find out what the particular needs of the agency are. Then, rather than being the go-between for the partner and the student, have the student and community partner establish that dialogue together and develop strategies for meeting a community need by capitalizing on the strengths of both partners.

Mobley believes respect for difference is equally as important. Students are not often prepared for situations in which they are face-to-face with someone from a different background who may be facing a dire personal issue. “These are real people,” Mobley explained. Students must be prepared to respect these differences, “to step outside that box of individualizing social problems and blaming the victim.”

Finally, Mobley stresses the necessity of looking upstream. She explained that the foundation for the advocacy model of service learning is built on the idea that there are deeper social problems that must be solved and policies that must be changed in order to make a true difference in society. According to Mobley, service is very important, but volunteers should essentially be trying to “put themselves out of business,” so to speak. Perhaps, then, the need for service learning would decrease if more focus were put on the causes of the issues.

The Advocacy Model in Action

For the past ten years, Mobley has taught Clemson’s sophomore Community Scholars course. Community Scholars is a four-year program that provides recipients with the opportunity to learn about civic engagement and community leadership while participating in various service activities throughout their time at Clemson. Mobley’s course focused more heavily on looking upstream, her third principle of service learning. The topics and readings covered allowed students to explore other models of service besides simply meeting basic community needs. Mobley tried to push students out of their comfort zone, bringing in articles such as “What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Service.” She said she wanted students to dig deeper, to listen with a different ear, and to think about how they can perform service with rather than for individuals.

One way Mobley put these ideas into action was through Tiger Talks, the overarching project in her Community Scholars course. The project drew inspiration from the idea-spreading nonprofit organization TED, which holds conferences at which speakers present “TED Talks” on a variety of topics. Similarly, the Tiger Talks project required students to develop their own story. Modeled after the “public narrative” approach developed by Marshall Ganz at Harvard University, the talks consisted of three parts, each about three minutes long. The first was the “Story of Self” in which students explained their current service in the community and how it connected to them in deeply personal ways. The second part, the “Story of Us,” was an attempt to connect with the audience’s overall values. Mobley asked students to make connections with what they all had in common with one another, especially as it pertained to the students’ own service endeavors. The third and final story was the “Story of Now.” This was where the idea of advocacy really came into focus. Students conducted research on social advocacy and promoted opportunities for action regarding their topic. The overall goal of this project was to encourage students to think differently about their service activities.

Your Voice Can Make a Difference: Mobley’s Advice for Other Faculty

The Tiger Talks project is just one example of how the advocacy model of service learning can be used on a college campus. Mobley encourages other faculty to explore this approach as well, though she admits that “when you incorporate something extra like this, it does take a little bit of effort and research.” According to Mobley, working with any kind of service-learning model is going to be slightly more labor intensive than teaching in a normal classroom setting. Traditional service learning requires cooperation with an agency partner to get students’ hours in, but the advocacy model requires a slightly different, more in-depth partnership with the agency. Incorporating this model might require a few extra meetings with agency supervisors to flesh out which policies they think need attention, what bills they are familiar with that are being considered and other more careful details.

It might sound like too much to realistically implement, but Mobley ensures that there are already plenty of faculty currently using this advocacy model on campus. Mobley praises the wide variety of resources available to help faculty move toward service-learning integrated approaches such as the Office of Teaching Effectiveness and Innovation and the Service-Learning Collaborative. “It really helps to connect with other faculty who are using service learning in this way to generate ideas and brainstorm,” Mobley said.

For Mobley, the extra effort is all worth it. “I hope students take with them a perspective that they can apply after they graduate,” she said. “They are going to move somewhere and get a job. They will be tax-paying citizens whose lives are affected by decisions made by other human beings.” Mobley explained that one of the most valuable aspects of her work with service learning and advocacy has been an increased sense of empowerment not just for herself, but for her students as well. She wants her students to know to look upstream when it comes to social issues because one day they might be in a situation where they have to advocate for their child or community or a cause they hold close. “Often, we live in our communities in a passive way — our lives get busy with work, family, and so much more,” Mobley said. “We feel disempowered when, actually, our energy and our informed voices can truly make a difference. After all, the root of the word ‘advocacy’ is ‘to voice.’”

Mobley seeks to give her students this voice and encourages other faculty to do the same.

Written By: Lauren Kirchenheiter

Lauren is a junior Communications major with a Sociology minor from Annapolis, Maryland. She loves books, dark chocolate, and traveling. Her interests lie in written and visual communications, social media strategy, and public relations.