Share This Article!

Related Articles

A Different Kind of Storytelling: Students get Creative in the Classroom to Promote Literacy

By: Marissa Kozma

As an actor, the first thing Acting and Theatre Appreciation Professor Kerrie Seymour tells her drama students is to think of the audience. Your responsibility is to engage that audience, and make sure that they believe you are telling the truth — the scene unfolding in front of them is real. The characters are real. This story, if only for a mere moment of your time, is actually quite believable. This is what makes for successful acting. But actors sometimes forget this. In the wake of auditioning and competing for the limelight, it is easy for some to get caught up in self-marketing and neglect to remember the audience’s importance. For Seymour and the nine students in her service-learning class “Literacy and Storytelling,” one of their goals is remembering to do just that. The solution? Four-year olds. “A lot of times actors have this reputation for being show-offs or for being really self-involved — always asking themselves, ‘What’s next for me?’ And so I thought that it would be a really great opportunity to engage our student actors in particular with the act of using their talents for someone else,” Seymour said. “I’m a person who believes that as an actor you are performing for the audience. It’s great for yourself too — it’s fun and it’s rewarding. Otherwise, we wouldn’t do it — but we do it to tell a story to other people. There is no way to be selfish when you’re reading a story for a child, and so I said there’s this need and I think theatre can help fill in a gap.” Seymour’s idea for the project came from other theatre companies she had heard of, and their own missions to spread community outreach — something that she learned Clemson didn’t have in the Performing Arts Department.

“I thought that it would be a really great opportunity to engage our student actors in particular with the act of using their talents for someone else.”

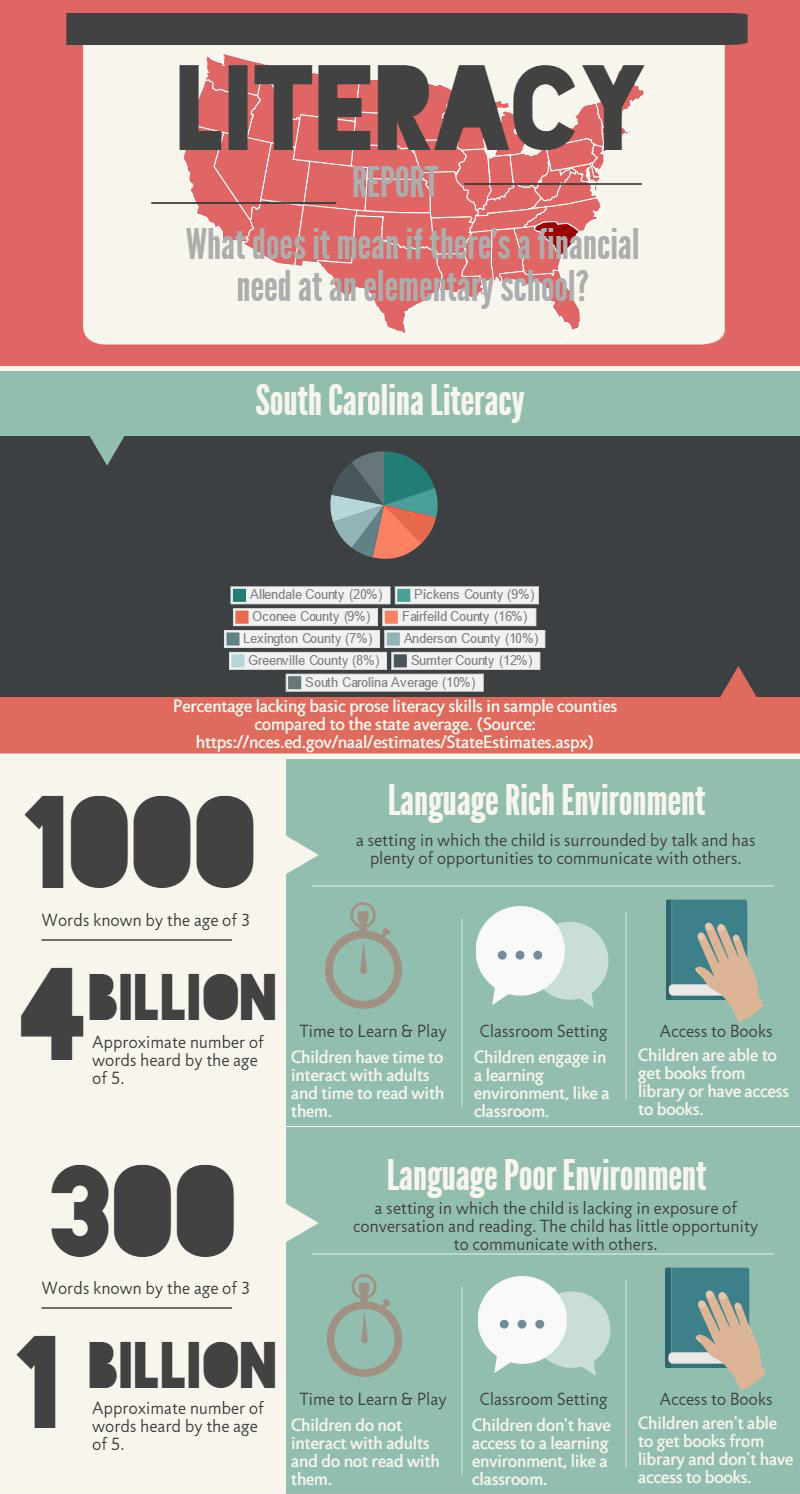

But it wasn’t until her own nine-year old son’s experience in school that she decided the main focus would be working with kids. Seymour’s son started at McKissick Elementary in Easley, and the transition from his former school in Greenville County was a drastic one. “As I was researching the school he was going to go to, I was seeing things like 76 percent of the students there get free or reduced lunch, and I started asking myself, ‘What does it mean when there’s financial need at an elementary school?’” Seymour said. Most of the students in the 4K classes that Seymour and her students are working with are need-based, meaning that they are considered at-risk for failure in school. Many of the children have learning disabilities, have a language apart from English as their primary language at home, and/or come from Seymour’s students read and act out a story to Central Elementary School. Seymour says she chose 4K classes specifically because 4K classes in Pickens County and throughout most of the state are need-based first. “Parents apply to join the 4K class, then they fill up the class if there are any other spaces left with non-need-based students,” Seymour said. Seymour expressed to her son’s teacher that she was concerned with the removal of the daily reading logs. She was surprised to hear that the reason was not because the teachers felt it was unnecessary, but because the children were having a hard time completing the assignment for a grade when their parents weren’t home to help them.

“Often times, having income problems has a link to having literacy problems and learning deficits,” Seymour said. “Usually not because of any lack of intelligence, but simply because the parents are working two to three jobs trying to keep the family afloat. So when do they have time to read to their kid?” The lack of reading time at night isn’t the only problem. Some of the children just don’t have available reading material at home. Parents in certain income situations may not know that the library is free, may have a hard time getting to their local public library, or may be worried about a 10 cent per day late-fee on overdue books.

“Owing 30 cents because I couldn’t get to library in time really does have a value in bread or milk and that never occurred to me,” Seymour said. “We live in the land of being fortunate.” Seymour also said that the numbers are astounding. “A student/child that is in a financially-rich environment or even a language-rich environment tends to, at the age of three, know more than 1,000 words. A child in a language-poor environment typically knows 300,” she said. “By the time a child is five in a language-rich environment, they’ve heard like three billion more words and it could be 700 ‘the’s’ but it’s still billions of words. It changes the way you communicate; it changes the way you read; it changes the way you speak.”

Seymour and her students want to change these numbers for their 4K classes in Pickens County, so they’ve begun getting the children engaged by making storytelling a bit more fun. Since most of the students in the classes are only just beginning to read, Seymour has her students practicing their acting skills on the four-year olds. She has them each select a children’s book to read aloud and act like they would any other script for a production. Seymour also tells her students that their performance skills are going to benefit from acting in front of the kids. “If they’re just reading it, they’re going to lose the children. They’re going to lose the four-year olds,” Seymour said. “They only have so much of an attention span.” Sophomore theatre major Katy Hinton believes that having kids in the audience is sometimes more exciting than performing for her peers and adults. “My favorite part about working with kids is how creative they are. They have no inhibitions and are always ready to try any game with no reservations, which is something that adults do not do. I think their creativity is why it is so wonderful to allow kids to explore the arts because odds are they’re going to create something unique and exciting,” Hinton said.

“My favorite part about working with kids is how creative they are. They have no inhibitions.”

The 10 books are rehearsed, and some of the students have even planned to wear costumes for their performances and have each other play different roles. Seymour has also had them create classroom activities to accompany each storytelling, so that the kids can become even more engaged. When asked about the structure of each reading, Seymour said that each book is different — one of the books is even catered to the bilingual students in the classroom and is read in both English and Spanish. In addition to the 10 book presentations planned for Clemson Elementary and Central Elementary School, Seymour and her students have also been doing other things for the kids.

Throughout the week of April 12, The Week of the Young Child, Seymour, her students and a number of volunteers hosted a marathon read and spent 24 hours reading to young people. Seymour and her students are also binding books that the children write themselves. “We’re trying to engage in as many ways as we can by storytelling and getting a child to not just hear books, but to actually engage with them — the same way you would engage in a story if you came into the theatre and were watching it unfold in front of you,” Seymour said. “We’re not teaching them to read, we’re teaching them to want to read. All actors are storytellers. It’s in our blood; that’s what we do. And we get to bring that love to so many kids who might not even know they love storytelling,” Seymour said.

Written By: Marissa Kozma

Marissa is a senior English BS major with a minor in Writing & Pedagogy. She has studied cultural and liberal arts in Paris and is a tutor for the Clemson Writing Center, as well as a student ambassador for the College of Architecture, Arts and Humanities.